Women and Madness

By Claire Jones.

The association of madness with 19C femininity has generated much research by historians of women’s history. Although this association can be traced back to medieval times, ed to woman mystics such as Julian of Norwich for example, it was in the Victorian era that madness became what has been called ‘a female malady’.

Table of Contents

Historians have found many accounts of female madness left by Victorian doctors, alienists (a contemporary term for doctors who specialised in mental disease) and early psychiatrists from their contributions to medical journals, patient records, reports, books and other publications. It is more difficult to find their female patients’ experiences, but one place to look is within the pages of countless novels, mainly written by women, which took female madness as a theme.

As well as novelists such as Charlotte Bronte (Jane Eyre, 1847) and Mary Braddon (Lady Audley’s Secret, 1862), other writers used their personal experiences to present semi-autobiographical accounts. Florence Nightingale’s Cassandra (1860) and Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s The Yellow Wallpaper (1892) both offer descriptions of women’s insanity and blame it on the confined intellectual and social lives that middle-class women were forced to lead. Similarly, Victoria Glendinning’s reconstruction of her great-aunt’s short life, A Suppressed Cry (1969, 2nd ed. 1975) tells the story of a ‘stifled’ daughter, an early student at Newnham College, Cambridge, who died at the age of 22 of what was probably asthma.

The feminization of madness

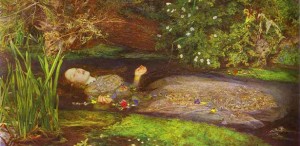

Ophelia by Madeline LeMaire (1845-1928) a French woman artist. LeMaire emphasise the sexual basis of Ophelia’s madness in her painting produced in the 1880s

The feminization of madness associated with the Victorian era is perceivable in art and painting as well as in literature. By the 1850s statistics were being collated that confirmed the perception that women were more likely to be incarcerated in asylums as inmates and, even more, ‘mad’ women came to dominate representations of madness. Yet prior to the late 18C madness was represented more usually as masculine. One example of the shift away from male representations of madness in art was the popularity for Victorians of images of Ophelia. Representations of Ophelia as childlike and golden gave way to more ambivalent images which also gave a hint of sexuality, such as in pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais’s famous painting exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1852. Ophelia was used as a specific ‘type’ of madness by psychiatrists at the time too.

The timing of this change to a female representation of madness must be understood in the context of changes in Victorian society and an increasing understanding of femininity as having sexuality at its core. Sexuality was the defining quality of woman’s nature – which is why codes of chastity, conduct books, sexual segregation after puberty, marriage and patriarchal social arrangements were so necessary to protect her and manage her ‘weak’ character and inclinations. The other side of the coin to the ‘weak, dependent women’ was, of course, the manly, strong, morally upright and disciplined man who protected her – the ideal Victorian type of male

Madness, women and the Victorian novel

Millais ‘John Millais’s Opehia (1851-2).

The women’s sensation novels of the 1860s were some of the chief literary sales successes of their day. A common theme was that of a respectable family with a dark secret or a grisly skeleton in the cupboard. Usually the story focussed on the domestic sphere; in particular the sensation novel dwelt on the secrets of women.

Most of Mary Braddon’s early novels were stories of women with a concealed past and many of her heroines were criminals, bigamists and/or murderers. Lady Audley’s Secret and Aurora Floyd (her two biggest sellers) are both bigamy novels. The two heroines embody and exploit the fear (which pervaded middle-class culture) that women were ‘wild beasts’ whose lusts and licentiousness ran riot if not constrained by the patriarchal family.

The plot of Lady Audley’s Secret reflected the contemporary medical theory that women were prone to madness due to reproductive instability, an instability which can be inherited by daughters from their mothers. Lady Audley’s strange actions date from the birth of her son and the onset of puerperal fever (childbirth was considered a time when women were particularly prone to mental instability). The question of Lady Audley’s madness – is she mad or simply wicked? – is one of the key dynamics of the narrative. It is resolved at the end of the book when she is incarcerated in a private lunatic asylum because she cannot be contained within the bounds of ‘proper’ femininity. She is ‘the angel in the house’ turned into ‘domestic horror’.

The plot of Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White (serialized 1859/1860) turns on two women being unjustly incarcerated in a private mental institution. These private asylums proliferated at mid century as alternatives to the established, large-scale public hospitals/asylums.

In Jane Eyre, Rochester’s first wife Bertha is the model of the ‘Mad Woman in the Attic’. She is described as sexual, unchaste and rebellious and refuses to conform to codes of acceptable feminine behaviour. As a result she is locked away, out of sight, condemned as ‘mad’.

Victorian psychiatry

Medical writing at the time made it clear that doctors’ believed women uniquely vulnerable to mental instability; protecting her involved regulating her sexuality and cycles. Mothers were advised to try and delay menstruation in girls and doctors sought to regulate women’s minds by regulating their bodies. Dr Isaac Baker Brown pioneered the surgical practice of clitoridectomy as a cure for female insanity which he carried out at his private clinic in London. One of his patients was only 10 years old and the ‘madness’ of several others consisted of their wish to take advantage of the new divorce act of 1857. Another young woman was brought to the clinic by her family because she had suffered ‘great irregularities of temper’, was too assertive in sending her visiting cards to men she liked and spent ‘much time in serious reading’.

Elaine Showalter argues that clitoridectomy was the surgical enforcement of an ideology that restricted female sexuality to reproduction, not least because it eliminated women’s sexual pleasure at a time when such pleasure was defined as a symptom of insanity.

Recommended Reading:

Lisa Appignanesi, Mad, Bad and Sad: A history of the mind doctors from 1800 to the present (Virago 2008)![]()

Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, The Madwoman in the Attic: The woman writer and the nineteenth-century literary imagination (Yale University Press, 1979)![]()

Elaine Showalter, The Female Malady: Women, madness and English culture 1830-1980 (Virago, 1985)![]() .

.

[…] how much of our definition of both is a historical and cultural construct. In her excellent article Women and Madness, Claire Jones looks at how Victorian women were often consigned to lunatic asylums for reasons […]